Access to Transport Services for People with Disabilities in Kathmandu

This article analyzes the current scenario regarding access to transport services for person with disability (PWD) in Kathmandu Valley. It describes the problems faced by people with disability in access to transportation and highlights the gaps between available policies and their implementation. Nepal has introduced several laws, policies and guidelines, including the recently promulgated People with Disability’s Rights Act, 2017, which establishes the rights forpersons with disabilities , include the right to mobility and the right to access all public facilities.

Nepal has also signed international conventions related to persons with disabilities which require the state to provide adequate facilities for universal access. However, in spite of a few initiatives, including the recently introduced disable-friendly buses by SajhaYatayat which have space and ramps for wheelchairs, Nepal still has a long way to go make universal access a reality and ensure that persons with disabilities can enjoy their constitutional rights. This journey could start by the government immediately formulating and enforcing Urban Street Standards with universal designs which are applicable for all citizens.

Key words: transport services; disability; accessibility.

Introduction

Persons with disabilities are a part of our society and they have rights just as other citizens. All of us will be temporarily or permanently disabled at some point in life, and those of us who survive until old age will experience increasing difficulties in functioning. Furthermore, most people have family members or friends who are temporarily or partially impaired in some way or another who may need assistance.

Access to transport infrastructure and services is important for employment, education, healthcare, and social and recreational activities for all. In the absence of access to transportation, persons with disabilities are more likely to be excluded from essential services and social interaction. Therefore, it is essential that our societies are sensitive to the needs of persons with disabilities and our cities are designed to ensure that their right to transportation and access to public spaces and services are not hindered in any way. In other words, cities need to be designed for universal accessibility.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over a billion people, or one in seven people or 15 percent of the global population, has some form of disability. The WHO further states that the percentage of persons with disabilities are increasing globally due to aging population and increases in chronic health conditions, among other causes. (WHO, 2017).

The official figures for the number of people with disability in Nepal is lesser than what WHO estimates, which may be because many people with some form of disability have not been identified as persons with disabilities. According to the 2011 Census, 1.94 percent of the total population of Nepal has some kind of disability. Although this estimate is much higher than the previous census from 2001, when the prevalence of persons with disabilities was estimated to be only 0.46 percent, it is much lower than the Nepal Living Standards Survey 2010-2011, which estimated that 3.6 percent of the population has some form of disability.

The Central Bureau of Statistics agrees that the quality of census data on persons with disabilities needs to be improved (Malla, 2012) and representatives of organizations working with persons with disabilities claim that the number of people with disabilities in the country is higher than the official records of the government (Lamsal, 2017).

According to the 2011 census, the number of people with disability in Nepal was found to be highest in Kathmandu district with 17,122 people, although in terms of percentage of the total population it was the lowest at 0.98 percent. In Lalitpur and Bhaktapur, 1.05 percent of the total population was found to have some kind of disability. In total, the three districts have over 25,000 people with disabilities. Although this is probably an underestimate, it is still a significant number and their needs to be addressed. Furthermore, many people are temporarily disabled, either because of illness or old age, which causes difficulties in their functioning.

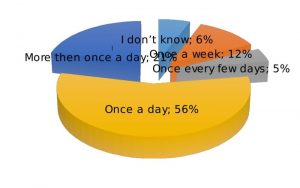

Mobility needs and related difficulties faced by people with disabilities, like other citizens, need to access public facilities such as schools, hospitals, markets, workplaces, and entertainment centers. The survey was conducted by Clean Energy Nepal for this paper among 84 people with disabilities in Kathmandu about mobility needs and problems faced regarding transportation in Kathmandu. Majority (77 percent) of the respondents of the questionnaire survey which included 50 wheelchair users, 27 persons with visually- impairment and seven persons with hearing-impairment, said that they had to travel outside their house at least once a day for various reasons and most them either walked/used wheelchair or used public transportation for their travel needs (Figure 1).

Walking/wheelchair was most commonly used for going to the market followed by going to school or workplace. Public transport was commonly used for visiting friends and relatives or places of worship or recreation. Only five of the 84 people surveyed said that they used car or taxi, while 10 said that they used disabled-friendly scooters with four wheels.

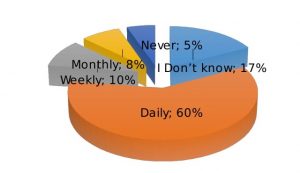

During the survey, 60 percent of the respondents said that they faced difficulties related to access to transportation on a daily basis (Figure 2). This clearly demonstrates the need for disabled-friendly transport facilities and services in Kathmandu. The respondents of the survey also mentioned the importance and need for convenient buses which they can board and get off easily, as well as bus stops with shelters. While 93 percent said that ease of getting on and off the buses was important or very important only 17 percent of the respondents said they were satisfied with this service. Equally important is the ease to cross the streets and access public transportation. While 92 percent of the respondents said that safety while crossing the street is important or very important, only 7 percent felt safe or mentioned that they were satisfied with the current condition of street crossings.

Besides the facilities, the attitudes and behavior of drivers, conductors, and other passengers of public transport were also found to be important for persons with disabilities. Almost all the respondents felt that the drivers and conductors of public transport vehicles need to be friendly and courteous and there should be no harassment. However, compared to the satisfaction level of facilities, more respondents said that they were satisfied with the behavior of the public transport vehicle staff as 52 percent said that they were satisfied with the behavior of drivers and conductors.

Another important need for people with disabilities is access to information regarding transportation systems. Over 51 percent of the respondents felt that the availability of reliable information was very important and 42 percent said it was important for them. However, only 19 percent of the respondents felt satisfied without the access to information about the transportation system and services in Kathmandu.

Many studies have shown that mobility can be a serious challenge for persons with disabilities as they face different types of obstacles and difficulties on the streets or public transport systems. The nature and extent of these difficulties vary according to the type of disability (IbGM, n.d.). People who are unable to walk usually use wheelchairs, but wheelchair users often face several obstacles on the road and public transport facilities. On the road, wheelchair users find it difficult to negotiate curbs, stairs, steep slopes, long road gradients, narrow paths and uneven road surface with potholes. Similar to public transport vehicles, obstacles for wheelchair users include narrow entrance, steps, and insufficient space to accommodate wheelchairs.

Furthermore, public transport services need to have accessible stops, counters, and information. Some of these difficulties can be overcome with assistance, but the need for assistance should be avoided if possible to promote self-determined life.

People those face mobility challenges may not need wheelchairs but they usually require a walking aid such as crutches or artificial leg. They face difficulties in crossing roads with high traffic volume and in overcrowded places. Because they may require putting in a lot of effort to walk, they often move slowly and may get tired more quickly thus requiring resting spots. Unlike wheelchair users, visually impaired people may not face physical challenges in overcoming steps and narrow passages, but they have difficulties in orientation. Like people with physical disabilities, visually-impaired people also face difficulties in crossing streets and crowded places.

People with cognitive and mental impairment often face many difficulties on the street and in public transport as they are generally not comfortable in unfamiliar environments and they adapt slower to strange situations. They may also suffer from orientation, concentration and memory disorders and some people with mental impairment often suffer from anxiety and panic attacks that may result in loss of control. People with Hearing impairment face difficulties in communication on the street and public vehicles, but physical obstruction of the streets or public transport vehicles may not cause major difficulties.

Policies and Legislation related to persons with disabilities and universal access

Over the years, Nepal has introduced several laws, policies, and guidelines establish the rights of persons with disabilities, including their right to access transportation facilities. Initially, the Disabled Protection and Welfare Act, 1982 and its regulations which only came 12 years later in 1994, looked at persons with disabilities through a welfare lens, but more recent policies and legislation look at disability from a human rights perspective.

The Constitution of Nepal, 2015 has guaranteed all citizens, including persons with disabilities, fundamental human rights, including the right to live with self-respect and access all public services and facilities. In addition, Section 4 of the Constitution, which lists the State’s directive principles, policies, and responsibilities, has a provision of safe, well managed and disabled-friendly transportation sector to ensure easy and equitable access to transportation services for all citizens.

The recently promulgated People with Disability’s Rights Act, 2017 further establishes the rights for persons with disabilities, include the right to mobility and the right to access all public facilities.

Nepal has also signed international conventions related to persons with disabilities which require the state to provide adequate facilities for universal access.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), which Nepal has signed and ratified in 2010, has a provision on Accessibility which states (UN, 2006): “To enable persons with disabilities to live independently and participate fully in all aspects of life, States Parties shall take appropriate measures to ensure to persons with disabilities access, on an equal basis with others, to the physical environment, to transportation, to information and communications, including information and communications technologies and systems, and to other facilities and services open or provided to the public, both in urban and in rural areas.”

The Convention further states that these measures, which shall include the identification and elimination of obstacles and barriers to accessibility, shall apply to, inter alia: Buildings, roads, transportation and other indoor and outdoor facilities, including schools, housing, medical facilities, and workplaces; Information, communications and other services, including electronic services and emergency services.”

Similarly, Article 20 of the Convention, which relates to personal mobility, states that Parties shall take effective measures to ensure personal mobility with the greatest possible independence for persons with disabilities, including by: Facilitating the personal mobility of persons with disabilities in the manner and at the time of their choice, and at affordable cost; Facilitating access by persons with disabilities to quality mobility aids, devices, assistive technologies and forms of live assistance and intermediaries, including by making them available at affordable cost; Providing training in mobility skills to persons with disabilities and to specialist staff working with persons with disabilities; Encouraging entities that produce mobility aids, devices and assistive technologies to take into account all aspects of mobility for persons with disabilities.

In order to implement the convention, governments and civil society members in the Asia Pacific Region agreed on the Incheon Strategy to “Make the Right Real” for a guiding framework for disability-inclusive development in the Asia Pacific region in 2012. The strategy has 10 goals 27 aligned targets and 62 corresponding indicators. Goal 3 of the Incheon Strategy is to “Enhance access to the physical environment, public transport, knowledge, information, and communication,” (UNESCAP, 2017).

Nepal has also signed the Sustainable Development Goals, which with its overarching objective of “leaving no one behind” addresses the needs of persons with disabilities is essential for meeting all the goals. While many of the goals can be linked to persons with disabilities, Goal 11 Sustainable Cities and Communities specifically deal with universal access. Two of the 10 targets within Goal 11, specifically mention persons with disabilities. SDG target 11.2 is to provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport, with special attention to the needs of persons in vulnerable situations, women, children, persons with disabilities and older persons by 2030. Similarly, SDG target 11.7 is to provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible green public spaces, especially for women, children, older persons, and persons with disabilities. Nepal will need to make significant investments in policies and public infrastructure in order to meet these targets of universal access. A recent review of progress on SDGs by the National Planning Commission does not include the review of Goal 11 (NPC, 2017).

Gap between policy framework and implementation

Although Nepal has some policies and legislation related to access to transport services for persons with disabilities, implementation remains weak. This is mainly because the policies have not been followed up by plans and investments and efforts have not been made to enforce the legal provisions.

The Five Year Strategic Plan for Road, Rail, and Transport Sector (2073-2078) recently prepared by the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport mentions that in urban areas all roads will be made pedestrian and disable friendly. But the Plan does not provide any further details on how this will be done or by when.

Design and construction of roads and other mobility related infrastructure in a country is normally governed by the Road Standards or Street Design Guidelines of that country. However, in the case of Nepal, the Nepal Road Standards, 2027 (NRS) mentions that it shall apply only for Strategic Roads in rural areas which are normally national highways, and for non-strategic (local Roads) and urban roads separate standards shall be considered. But, Nepal does not yet have any standards or guidelines for local or urban roads.

Therefore, there are no standards or guidelines which can or should be used in designing urban and local roads. However, the NRS does have a few provisions for urban streets. For example, in the case of footpaths in cities, it says, “Width of the footpath depends on the volume of anticipated pedestrian traffic. But a minimum width of 1.5 m is required.” However, it should be noted that the pavement width of 1.5 m is not sufficient for two wheelchairs to pass one another. For this, a minimum of 1.8 m would be required.

Similarly, the NRS also mentions that “all overpass or underpass pedestrian crossings should be provided with a ramp for wheelchairs or other alternative measures (e.g. lifts) for comfortable movement of people with disabilities.” It also mentions that the maximum grade on the ramps should not be steeper than 8 percent. However, the Guidelines for Access to Physical Facilities and Information for People with Disabilities, 2069, which was approved by the government in 2013 mentions that ramps should have a slope of 1:15, which is 6.7 percent (MoWCSW, 2012). These guidelines, which are not mandatory, have detailed specifications for wheelchair ramps, parking spaces, and other facilities. This together with other international standards can be used to upgrade the Nepal Road Standards or prepare an Urban Roads Standards to ensure persons with disabilities’ right to access transportation services.

Different countries have introduced legislation and standards to ensure universal access to transport. In the US, The Department of Justice (DOJ) revised the Americans with Disabilities Act, 1990 (ADA) in 2010 and published Standards for Accessible Design. It has also compiled Guidance for the 2010 standards and many cities have prepared manuals based on these standards.

For example, the Street Design Manual of New York City states that “Projects should meet all applicable federal, state, and or local accessibility standards for public rights–of–way, including minimum clear sidewalk widths, inclusion of ADA–compliant pedestrian ramps, and provision of accessible waiting and boarding areas at transit stops.” It also states that “Sidewalks must conform to ADA requirements for minimum clear path width and provision of spaces where wheelchair users can pass one another or turn around; beyond the ADA minimum, provide an unobstructed clear path of 8 feet or one–half the sidewalk width, whichever is greater (NYCDOT, 2009).”

In India, Persons with Disabilities Act, 1995 (Sec 44) recommends guidelines for persons with disabilities. In this context, different cities have introduced guidelines to promote universal accessibility. For example, one of the goals of Delhi Street Design Guidelines is to ensure universal accessibility and amenities for all street users by following universal accessibility design standards to make public streets and crosswalks fully navigable by the persons with physical disability. It has a section on Universal accessibility which has details for curb ramps, road crossings, tactile paving, auditory signals and accessible infrastructure (DDA, 2010). Similarly, Pune’s Urban Street Design Guidelines has a dedicated chapter on Universal Accessibility and Disable Friendly Design (PMC, 2016). These guidelines can be useful for Nepali cities to develop their own standards and guidelines.

The gap between policy and practice is, however, not unique to Nepal. A survey of 114 countries done by the UN in 2005 found that while many had policies on accessibility, they had not made significant progress in implementing these policies. Among the surveyed countries, 54 percent reported that they did not have accessibility standards for outdoor environments and streets, 43 percent had none for public buildings, and 44 percent did not have them in schools, health facilities, and other public service buildings. Furthermore, 65 percent had not started any educational programs, and 58 percent had not allocated any financial resources to promote universal accessibility. Similarly, although 44 percent of the country had a government body responsible for monitoring accessibility for people with disabilities, the number of countries with ombudsmen, arbitration councils, or committees of independent experts were very low (South-North Centre for Dialogue and Development, 2006).

Experiences from other countries indicate that accessibility is more easily achievable incrementally in all stages. Initial efforts should aim to build awareness and a “culture of accessibility.” Once the concept of accessibility has become ingrained or institutionalized, it will become easier to raise standards and attain a higher level of universal design. Recently, the community in Jorpati area of Kathmandu had initiated a small project to make 100 meter stretch of the main road in Jorpati disabled-friendly (CEN, 2013). Although this project was not completely successful in constructing the street as per design, it has raised awareness and demonstrated how it is possible to make existing streets disabled-friendly with little investment.

Case Study: Khagendra Accessible Road Project in Jorpati, Kathmandu

As a large number of persons with disabilities live in the Jorpati area of Kathmandu, the local community in collaboration with Khagendra New Life Center and Spinal Injury Rehabilitation Center initiated the Khagendra Accessible Road project do demonstrate an access road in 2011.They raised funds locally and designed a100-meter stretch of a disability-friendly road with accessible sidewalks and other facilities. They also managed to convince the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport to partly invest in the project and implement it. This project was expected to benefit more than five thousand people with disabilities. The total estimated cost for the project was Rs. 1.8 million. The community rose about Rs. 0.6 million locally and handed it to the Department of Roads for construction. However, the contractor hired by the Department did not do a very good job. Although today the road is far from ideal, local persons with disabilities say that it is still a good start and many uses this stretch on a daily basis for their shopping and other purposes.

Recently, SajhaYatayat has introduced a few disabled-friendly buses in Kathmandu which are equipped with ramps and the doors and the gangways are wide enough for wheelchairs. The buses also have space for parking and strapping wheelchairs. This is a good initiative which can be a good example for other public transport operators as well. In addition, this may also encourage the government to make the bus stops and roads disabled-friendly as well.

Way Ahead

While Nepal has made some progress in formulating policies and legislation related to access to transportation for people with disabilities, it still has a long way to go make universal access a reality and ensure that persons with disabilities can enjoy their constitutional rights. This journey can start by taking the following initial steps:

As Nepal is a rapidly urbanizing country, the government’s Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and transport needs to immediately formulate and enforce Urban Street Standards with universal designs which are applicable to all citizens.

All stakeholders, particularly related government and municipal officials, engineers and contractors need to be trained on Universal Design of streets and public facilities.

Government should work in partnership with local governments, public transport operators and local communities to make major streets and public transport systems in cities disable-friendly.

References

- CEN, (2013).Walkability in Kathmandu Valley, MAYA Factsheet #2, Clean Air Network Nepal Clean Energy Nepal,Kathmandu.Retrievedromhttp://www.cen.org.np/uploaded/Walkability%20in%20KV_MaYA%20Factsheet%202.pdf

- DDA, (2010). Street Design Guidelines, Delhi Development Authority, New Delhi.

- DOR, (2013).Nepal Road Standards, 2027 (Third Revision 2070), Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport, Government of Nepal, Kathmandu. Retrieved from http://dor.gov.np/home/publication/general-documents/nepal-road-standard-2-7

- IbGM, (n.d.): Survey on information for people with reduced mobility in the field of public transport.

- Malla, U.N. (2012) Disability Statistics in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, Kathmandu.

Lamsal, P. (2017) Data disaggregation by disability to leave no one behind. Retrieved from http://www.globi-observatory.org/data-disaggregation-by-disability-to-leave-no-one-behind/ - MoPIT, (2015): Road, Rail and Transport Development for Prosperous Nepal: Five Year Plan (2073-2078), Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport, Government of Nepal (in Nepali), Kathmandu. Retrieved from http://www.mopit.gov.np/links/18a9c324-217b-4d98-a96e-69c16f10d3de.pdf

- MoWCSW, (2012) Guidelines for Access to Physical Facilities and Information for People with Disabilities, 2013 (in Nepali), Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare, Government of Nepal, Kathmandu. Retrieved from

- अपांगता भएका व्यक्तिका लागि पहुँचयुक्त भौतिक संरचना तथा संचार निर्देशिका २०६९,

- NPC, (2017).National Review of Sustainable Development Goals, National Planning Commission, Government of Nepal.Kathmandu. http://www.npc.gov.np/images/category/reviewSDG.pdf

- NYCDOT, (2009).Street Design Manual, New York City Department of Transport, New York City. Retrieved from http://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/html/pedestrians/streetdesignmanual.shtml

- PMC, (2016) Urban Street Design Guidelines Pune Municipal Corporation, Pune. Retrieved from https://pmc.gov.in/sites/default/files/miscellaneous/USDG-FD-UploadingFile.pdf

- South-North Centre for Dialogue and Development, (2006).Global survey on government action on the implementation of the standard rules on the equalization of opportunities for persons with disabilities. Amman, Office of the UN Special Rapporteur on Disabilities, 2006:141.

- UN, (2006).The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and its Optional Protocol, United Nations, New York. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

- UNESCAP, (2017).Building Disable-Inclusive Societies in the Asia Pacific Assessing Progress of the Incheon Strategy, UNESCAP Bangkok. Retrieved from http://www.unescap.org/publications/building-disability%E2%80%91inclusive-societies-asia-and-pacific-assessing-progress-incheon

- Wagle P.R. (2017), The Sustainable Development Goals: An opportunity for the persons with disabilities. Retrieved from https://www.nfdn.org.np/papers/sdg-opportunity-for-pwds.html

Author’s Bio

Bhushan Tuladhar is the Regional Technical Advisor South Asia for UN-Habitat’s Urban Basic Services Branch. He has a Masters in Environmental Engineering from Cornell University, USA and 25 years of experience of working on various urban and environmental issues in government, municipalities and NGOs. He headed the Environment Department of Kathmandu Metropolitan City and was a member of the City Planning Commission. Based in Kathmandu, Nepal he has led projects on water and sanitation, climate change, mobility, energy and waste management. He is currently a Board Member of SajhaYatayat, a public transport cooperative and Chairperson of Environment and Public Health Organization (ENPHO).